On shipyards and sea monsters

Holding tight to what's real in this season of political storms.

It’s now over a week since the assassination attempt on Donald Trump, and much ink has been spilt on its significance. Of the copious entries on the topic, I found two in particular worth reflecting on—not so much for news or even commentary, but for their insights into the stance appropriate to a grounded human being in times of political turmoil.

The first was “Men of courage, men of cowardice,” in which Alexander Brown of Acceptable Views described how this event, tragic though it was, failed to disrupt the tableau of everyday life on the BC Coast on a Saturday:

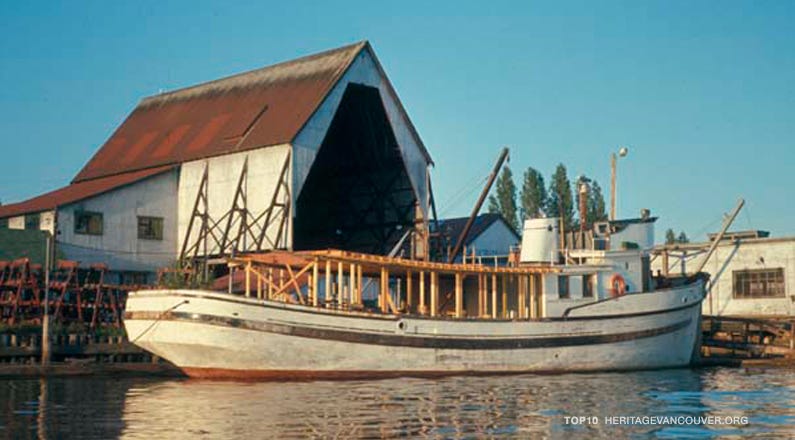

In a real-life case study into “the Particularly Online and the Very Political don’t entirely inhabit real life,” the missus and I were strolling through a turn-of-the-century British shipyard at the mouth of the Fraser River when the news broke. Boardwalk re-enactors didn’t break kayfabe. Families posed for photos. Fishermen continued to hawk the catch of the day. Pensioners guzzled crab legs and overpriced Okanagan wines.

Things were different on X, of course, where the collective id was at full throttle, with minute-by-minute updates and the usual pundits teeing up tedious commentary on the demise of democracy if “people” didn’t begin minding their political rhetoric.

But there is also a larger insight in Alex’s observation. Namely, who is and is not likely to keep their wits about them in a political calamity? Not the Twitter wordsmiths and warriors, it turns out, but those anchored firmly in real life:

Those who still exist in the real world, who have some degree of regulatory powers over the jet stream of neverending bullshit that runs through us each day like a dental x-ray, were able to stay grounded, and empathetic, and to compartmentalize tragedy over partisanship. There was no need to send out blathering remarks riddled with qualifiers and empty rhetoric featuring the new comms-shop buzz-term of the day: “political violence.”

Point taken, and extended. If we are to survive the upcoming political season, our best hope to safeguard our humanity may well be to limit the daily deluge from the screen.

That same Monday, on distant Irish shores, Paul Kingsnorth of The Abbey of Misrule arrived at a similar place from a different direction. In short order, he stripped the past weekend’s images down to their meaty bones.

In “All the World is Myth,” Kingsnorth linked that photo of a bloodied, defiant Trump flanked by his Secret Service protectors under the flag to a prior one:

Which image in turn linked to a prior one, and another, and has moved the human soul to its depths since time immemorial:

Because I don’t think it is politics we are dealing with here, or culture even. These things are the surface manifestation of the myths that writhe and turn beneath them. On the surface, sometimes, a fin breaks the water. Beneath, something huge is swimming.

To put that another way: everything is myth.

The image of the unbowed, flawed hero who would save/destroy us is an image from the myths of old.

So now what? Here the post takes a surprising turn. A devoted pilgrim of Orthodox Christianity, Kingsnorth presents the naked irruption of myth as a harbinger of manipulation and, as such, temptation.

And calls us to make a change:

Change your mind. Change your heart. Change your direction. Change the orientation of your seeing. Change your whole life.

Repent.

What do we do when we see the myth break the surface? We do this. We put not our trust in Princes. And we watch out for the Devil.

Stark words, I thought a week ago. Then thought of them again as I saw waves of cancel culture unfurl over the next days—the demonically gleeful doxxing of those unregulated souls who had taken to social media to wish death on a President.

Which is a sordid way to act. All of it. Sure, getting a Home Depot employee fired for wildly intemperate comments online uses the other side’s cancel culture rules against “one of them.” Sure, the doxxees may have subscribed to those rules; some may even have tried to cancel others in the past. But this does not change its ugliness, or that agitating to have people fired for statements made online plays straight into the hands of those who would normalize social policing of the internet. Yet there it was, the doxxing, spreading like wildfire on a hot Prairie day.

So yes, let’s repent. Nowhere does this lust for revenge end well.

Where I part ways with Kingsnorth—at least somewhat—is this remark (made at the level not of argumentation but of faith):

If, in response to whatever image the world throws at us, we look at our hearts, we can see instantly if peace dwells there, or something else: anger, rage, righteousness, distraction, even joy. If it is not peace, then something, or someone, is leading us astray.

On this point, this lapsed Roman Catholic takes exception. I do take seriously the advice to take stock of emotions twinged by myths put before us—and to consider the strong possibility of their manipulation. Yet states of being besides peace can also have a positive purpose. If channelled, they can inform—at times, even lead—a rejection of an intolerable status quo.

I’m also more sanguine on myth itself, a topic I wrote on at length many years ago. Myth not only stirs but soothes, gives our small individual lives larger significance; myth ties us to our communities, guides us to act in the world.

I think of the family of the man who went down, whose name we did not even know until the next day. An innocent bystander had taken a bullet intended for the former President and fallen through the bleachers.

Corey Comperatore was collatoral damage of an assassination attempt on Saturday, July 13, 2024 in West Pennsylvania. His was a random, avoidable political murder in our season of political storms. Let’s pray that it will be the last. Let’s hold fast to what happened and call for answers.

But let’s not reject the soothing balm of myth either. Through it, his death became a sacrifice. That ancient image now prevails, lending sense and purpose—for his family, the witnesses, all of us.

I’d like to appreciate the call to repent and also give myth its due. With healthy fear and respect, we can still let those old stories work on us, ennoble us, help us act well in this world—in the hope of realizing a better day.

Suggested Reading:

Alexander Brown:

Paul Kingsnorth:

We are overwhelmed with images and words! I don't watch the news and I find myself unsubscribing from one writer after another. It is just too much. I keep half an eye on it but it feels like it is all a distraction. A world is created and then we all look at it and talk about it, and lose precious beautiful moments on earth. I have noticed that a few of the writers I have followed are turning to religion,or let's just say, using terms like darkness and the devil. It's not for me, never could get behind the Jesus myth, but I do believe in love, and that's what will keep us sane and strong.