Two weeks ago, my sister and I took a road trip through the American Midwest. We headed down toll roads and up a sky way; stopped in four large cities; checked out a few casinos on Indian land.

The trip was long, but never dull. There’s a palpable energy in American cities—a constant spontaneous human interplay that is rarer in our more frigid climes. Yet just as visible is the decline: scars from the 2020 riots, the ramped up migration, the urban decay that set in decades ago.

Energy and entropy—how will it end? What will become of Detroit, with its pristine yet curiously empty downtown? Or of Minneapolis, with its destroyed city blocks down Lake Street? What will become, for that matter, of the United States of America?

Historical speculation is a staple of our Western culture. In fact, history is used to frame and tee up policy more often than we may realize. Common uses of history these days move on two lines:

Summoning historical specters to dissuade from a present path.

Instituting measures to bring forward a shining (yet shifting) goal of history.

Examples appear below, as well as thoughts on responsibly using history for policy .

History as Portent: “Are We Rome?”

The questions of the American republic’s demise and its potential causes were discussed already at its founding. The Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776. The written Constitution, the longest surviving one, was ratified in 1788. The same years saw the release of Gibbon’s six-volume History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Steeped in Roman history and legal theory themselves, the American founders took pains to structure the new republic on lines deemed to avert a similar descent into corruption and tyranny.

In other words, the fate of the Roman republic was a live issue in the 1780s.

To this day, American public intellectuals compare the United States to Rome. In 2007, for example, Cullen Murphy, editor at large for The Atlantic, published a book: Are We Rome? The Fall of an Empire and the Fate of America.

In 2021, he again asked, “No, Really, Are We Rome?” The article then blends the two settings thoroughly:

The scenes at the Capitol on January 6 were remarkable for all sorts of reasons, but a distinctive fall-of-Rome flavor was one of them, and it was hard to miss. Photographs of the Capitol’s debris-strewn marble portico might have been images from eons ago, at a plundered Temple of Jupiter. Some of the attackers had painted their bodies, and one wore a horned helmet. The invaders occupied the Senate chamber, where Latin inscriptions crown the east and west doorways. Commentators who remembered Cicero invoked the senatorial Catiline conspiracy. Headlines referred to the violent swarming of Capitol Hill as a “sack.”

Outside, a pandemic raged, recalling the waves of plague that periodically swept across the Roman empire. . . .

The debasement of truth, the cruelty and moral squalor of many leaders, the corruption of basic institutions—signs of rot were proliferating well before January 6, and they remain, though the horde has been repelled.

Colorful, certainly, but is it helpful as political analysis?

Lest we assume that Rome’s fall is the province solely of left-leaning imaginations, there is also this 2023 entry by E.J. Antoni and Peter St. Onge for the conservative Heritage Foundation: “Has America Entered the Fall of Rome?”

New York was once the greatest engine of prosperity in the world, and now people are fleeing in droves. We haven’t quite gotten to cows grazing in the Roman Forum, but entire swaths of once-thriving cities are now abandoned. Even the inhabited cities are in decline, with rising taxes outpaced by the crumbling institutions they allegedly fund.

Left behind is lawlessness, dying communities, and a two-tiered society with the lower class living in progressive misery and insecurity while the rich retreat to luxurious enclaves.

Like Rome before it, New York is a valuable warning to America at large because our nation has been heading the same direction as New York City—just moving slower.

The article then points to fatal errors of ruling elites in ancient Rome, now also evident in America.

The Fall of Rome presents a grand, tragic spectacle that has haunted the American republic since its founding. There are many other historical disasters to be used, of course. Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler is a current favorite.

The goal in examining this use of history is less to deride than to point out the rhetorical trick at play. The author invokes a historical precedent rife with ominous significance. The comparison culminates in a specific policy proposal. In this case, history sets up policy, saying: “We are at a crossroads. We can continue down the doomed path of X, or take this path—and survive.”

Beware the end of history

A second common use of history understands it as progress toward an end point. In this view, the cardinal sin is to “go backward,” to regress—by electing a conservative party, for example, or implementing a conservative policy.

A progressive use of history pervades the language of our current federal government. Among the Liberal Party of Canada’s X posts, for example, are gems like this January 2024 video clip:

“The difference is clear: while Pierre Poilievre wants to take Canada backward, we’ll keep Canada moving forward—for everyone.”

The same clip offers policies deemed to keep Canada “moving forward,” warning of dire consequences of electing those who will not.

Thus Prime Minister Trudeau. Yet it’s crucial to understand that the progressive goal of history is a moving target—and has been for centuries.

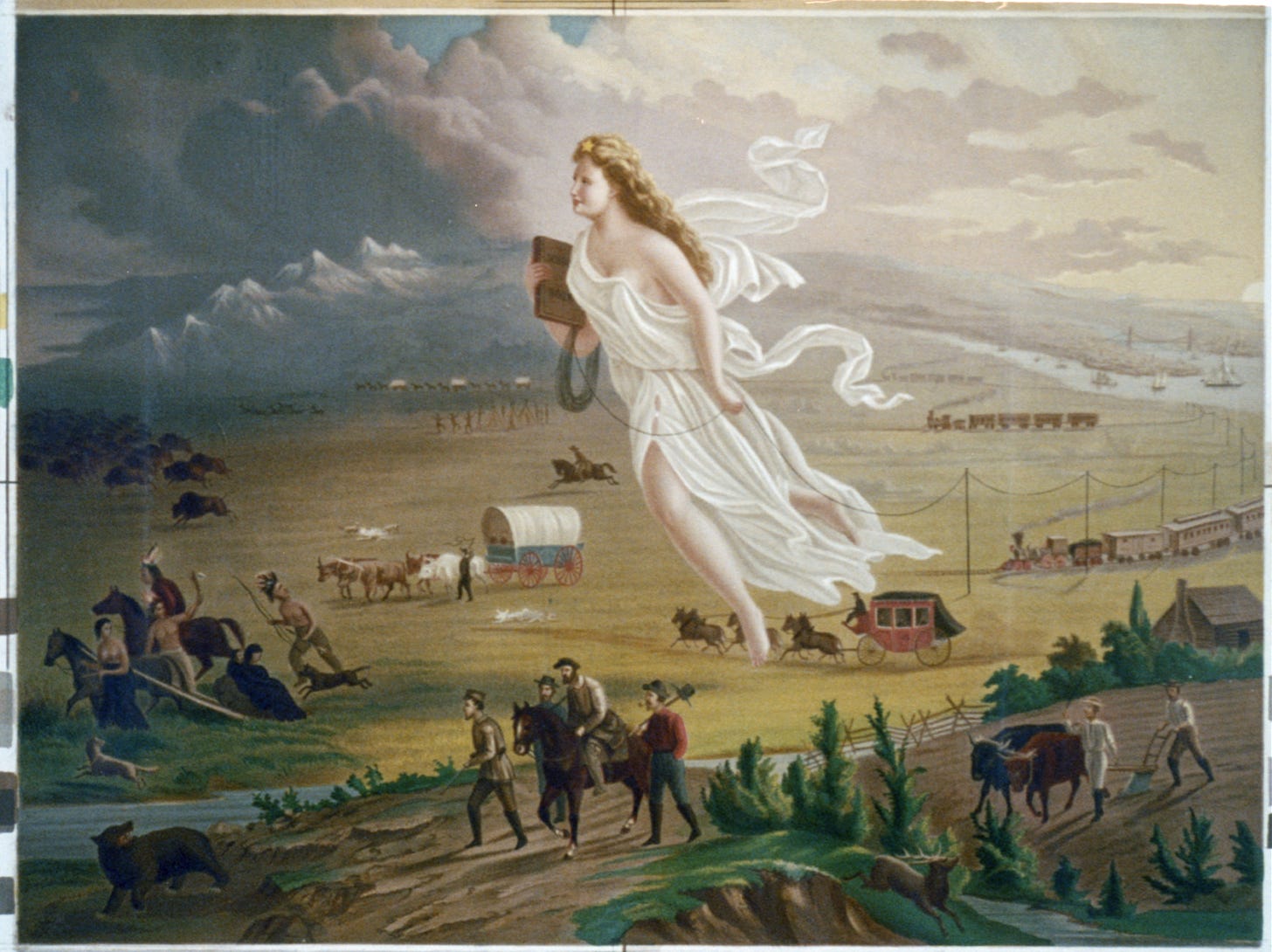

Today in North America, the goal is commonly seen as “social justice,” embodying tenets of diversity, equity, and inclusion. But it wasn’t always. In the mid-nineteenth century, progressives in both Europe and America deemed the goal of human history to be the advance of “civilization” over “barbarism”—as described, for example (only partly critically), by liberal political theorist John Stuart Mill in his 1836 essay “On Civilization.”

President Andrew Jackson, the first president of a new Democrat party, invoked progress in his 1830 State of the Union address to justify the newly passed Indian Removal Act:

It [the removal] will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.

The same view of progress prevailed into the early twentieth century. In 1914 in Canada, for example, Duncan Campbell-Scott, the longtime Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, sought an amendment to the Indian Act that would made it illegal for “an Indian to participate in any stampede in aboriginal costume outside his own reserve.” In a 1916 letter cited by L. Salem-Wiseman, he explained:

The purpose of the amendment to the Act was to prevent the Indians from being exploited as a savage or semi-savage race, when the whole administrative force of the Department is endeavouring to civilize them.

Note the easy use of coercion in both cases—buttressed by confidence in both the policy goal and the selected means to bring it about.

So where does this use of history leave us? Present-day progressives apologize for human rights abuses committed by the progressives of prior centuries. Only much later did they understand that the historical mission to advance civilization was not merely mistaken, but even genocidal.

Consciously or not, the progressive use of history for policy is supremely prone to abuse. For those who know the goal of history, it is a small step to open coercion of people who are deemed “backwards” or who do not sufficiently appreciate the goal.

In the limit, it is history used as a bludgeon.

What Then?

So how to use history responsibly to inform policy? With care, I suggest, and humility.

The humility piece is crucial. It is also honest. By contrast to the truth, history is a story—several, in fact—and we don’t know which stories will prevail in the end. More fundamentally, we are all enmeshed in our own and can never fully transcend them.

Arrogance about history presents itself as superior knowledge of the goal, direction, or lessons of history and the policies needed to realize them.

Humility about history sees our thinking about it as speculative, tentative. If a goal of history is known, it is through faith rather than human knowledge.

Consider this favorite citation of President Barack Obama, who reportedly had these words from Martin Luther King Jr. woven into a carpet at the White House:

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Now here is the same quote in context, in Dr. King’s 1967 address to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference:

When our days become dreary with low-hovering clouds of despair, and when our nights become darker than a thousand midnights, let us remember that there is a creative force in this universe working to pull down the gigantic mountains of evil, a power that is able to make a way out of no way and transform dark yesterdays into bright tomorrows.

Let us realize that the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. Let us realize that William Cullen Bryant is right: “Truth, crushed to earth, will rise again.” Let us go out realizing that the Bible is right: “Be not deceived. God is not mocked. Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.” This is our hope for the future, and with this faith we will be able to sing in some not too distant tomorrow, with a cosmic past tense, “We have overcome! We have overcome! Deep in my heart, I did believe we would overcome.”

Dr. King’s confidence is a prayer, his hope an article of faith.

How to use history for policy? With that crucial stance of humility, we can speculate as we like, observe patterns and precedents to help understand present circumstances. We can have faith that truth will prevail. We can uphold principles that we believe transcend history, ones others may consign to irrelevance.

And from there, God willing, we can forget history and simply do the right thing.

Here and now, in the present.

I like the quotes you’ve chosen, Jodi, to illustrate the misuse and abuse of history in the service of policy.

And I REALLY appreciate your point about the changing definition of “progressive”: what’s championed as progressive policy at one historical moment is later condemned by progressives of another historical moment. Of course, who gets to decide the meaning of progressive at any given time? My view: meanings are neither static nor are they uncontested; they always involve a contestation of power and beg the question, Whose interests are being served (political, economic, or moral) by a particular progressive discourse?

Which leads me to that familiar aphorism that history repeats itself. I grit my teeth when I hear that phrase. I find it interesting that Cullen Murphy uses it to suggest he’s concerned about the abuses of power. Yet it seems to me he’s using it in the service of power. How so? Because a comparison is never only about similarities. It’s also about differences. And tracing out differences, as any historian concerned with abuses of power will tell you, is important because they point to how historical outcomes are never inevitable. How convenient then that he elides difference with his simple conflation of disaffected protesters in 21st century America with barbarian “hordes.”